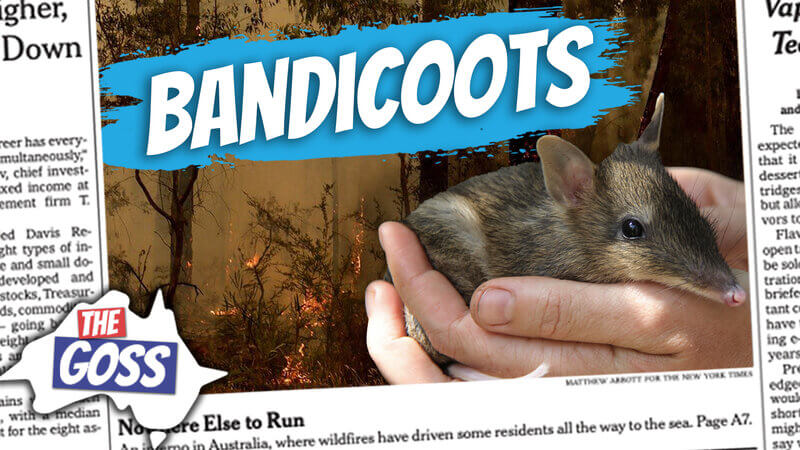

AE 1029 - THE GOSS:

Rewilding Bandicoots, The Hollowhog Invention, & Why Eucalypt Forests Have Evolved To Burn

Learn Australian English by listening to this episode of The Goss!

These are conversations with my old man Ian Smissen for you to learn more about Australian culture, news, and current affairs.

In today's episode...

How’s the week going, you mob?

Today, we’re talking about fascinating animals and trees in Australia!

One story is about bandicoots — these are marsupials; like kangaroos and wallabies; they just don’t walk with their rear legs. Each time they dig, these little rat-looking animals contribute to the health of the ecosystem because this way, the soil catches more water and nutrients.

Another story is about the adorable squirrels! A recent study by the University of California claims that squirrels have personality types, like humans.

We also have another story about the Hollowhog. Designed by Matt Stephens from NSW, it’s a wood carving tool designed to make holes in trees so that animals can live inside it.

And lastly, we talk about eucalyptus trees. A very unusual feature of eucalyptus trees is that they need fire to release their seeds, so you can actually help them by setting them on fire!

Improve your listening skills today – listen, play, & pause this episode – and start speaking like a native English speaker!

Watch & listen to the convo!

Listen to today's episode!

This is the FREE podcast player. You can fast-forward and rewind easily as well as slow down or speed up the audio to suit your level.

If you’d like to use the Premium Podcast Player as well as get the downloadable transcripts, audio files, and videos for episodes, you can get instant access by joining the Premium Podcast membership here.

Listen to today's episode!

Use the Premium Podcast Player below to listen and read at the same time.

You can fast-forward and rewind easily as well as slow down or speed up the audio to suit your level.

Transcript of AE 1029 - The Goss: Rewildling Bandicoots, the Hollowhog Invention, and Why Eucalypt Forests have Evolved to Burn

G'day, you mob. Pete here, and this is another episode of Aussie English. The number one place for anyone and everyone wanting to learn Australian English. So, today I have a Goss' episode for you where I sit down with my old man, my father, Ian Smissen, and we talk about the week's news whether locally down under here in Australia or non-locally overseas in other parts of the world.

Okay, and we sometimes also talk about whatever comes to mind, right. If we can think of something interesting to share with you guys related to us or Australia, we also talk about that in The Goss'. So, these episodes are specifically designed to try and give you content about many different topics where we're obviously speaking in English and there are multiple people having a natural and spontaneous conversation in English.

So, it is particularly good to improve your listening skills. In order to complement that, though, I really recommend that you join the podcast membership or the academy membership at AussieEnglish.com.au, where you will get access to the full transcripts of these episodes, the PDFs, the downloads, and you can also use the online PDF reader to read and listen at the same time.

Okay, so if you really, really want to improve your listening skills fast, get the transcript, listen and read at the same time, keep practising, and that is the quickest way to level up your English. Anyway, I've been rabbiting on a bit, I've been talking a bit. Let's just get into this episode, guys. Smack the bird and let's get into it.

Alrighty. So, dad, what's going on?

Hey, Pete. Bandicoot, squirrels and tree hollows.

I just realised that I didn't read the bandicoot or squirrel story but sent them to you, but I read the tree hollow one.

The tree hollow one... (both talking) ...I think the bandicoots a new one, you probably saw it as well, but.

Yeah... (both talking) ...The eastern barred bandicoots, and they were...

As we used to call them. Well, this, yeah, this story, eastern barred bandicoots. They come from- They're called eastern because they're obviously from the eastern states, mostly in Victoria. Ironically, they come mostly from western Victoria, but that's neither here nor there.

And for those of you who don't know what bandicoots are, they are small marsupials vaguely related to kangaroos and wallabies, but they don't hop around the same way on their back legs. They're sort of four legged, hoppy, more like a- A bit like a rabbit. They're the marsupial analogy of a rabbit.

Or a pig, right? Because don't they eat a lot of truffles and...

They do, yeah. So from eating, but they're small.

Yeah. Well, smaller than- A small, rabbit sized...

Teapot pig. Little...

So, these little guys, the eastern barred bandicoots were declared extinct in the wild about 25 years ago. I was working at Melbourne Zoo 30 years ago when the recovery programme for them started, and most of that involved creating areas that they were fenced to keep cats and foxes out.

And then people realised that the population was so small that the only way they were ever going to, you know, be maintained was to basically capture everyone that was in the wild. And there were very few of them at the time and put them into a captive breeding programme in zoos Victoria, so Melbourne Zoo, Healesville Sanctuary.

And they have been re-released into the wild over that period of time. I think they've now bred up about 1,200 of them, released them into the wild. And it's the first time ever that an animal that was previously declared extinct in the wild has been downgraded to endangered...

What probably wouldn't be... It wouldn't... Yeah, it might be in Australia, there's been a whole bunch of those animals that have been found to be, what thought to be extinct, and then they're found. There's one crazy one in the US, right, was it the- It was a ferret, right? Was it the black footed ferret?

Black footed ferret.

Yeah, where some farmer ended up stumbling across...

...Haven't seen one for 50 years and then some farmer comes across a little tribe.

Yeah...

Yeah, so that's a bit different where that was just, we haven't found them.

Yeah.

Which is typically, you know, extinct means, you know, not seen in the wild for 50 years, I think is the technical definition that is used in conservation groups. And there are occasionally those that, you know, all of a sudden, they're found again, in this case, they have never been found in the wild in that 30-year period.

Yeah.

Since they, you know, took the last ones. And but now they are there, and they're established, and they've moved away- I say they, the recovery teams have moved away from putting them into protected areas because it just wasn't working. And it was extremely expensive to create an area big enough to maintain a population of them and fence it to be effectively predator proof.

And now they are putting Maremma dogs in with them, the same as the famous ones from Warrnambool, with the penguins keeping foxes away. Because the Maremmas are a breed of sheep dog, but they're not herding dogs, they are used by shepherds to protect them. They basically just leave them out in the wild with sheep, particularly during lambing season, to keep foxes and wolves away in Europe, we don't have wolves in Australia.

But the same principle now works to keep them away from these endangered populations. Originally of penguins on an island in a, you know, in Victoria and now in the areas where they're releasing these bandicoots and they're actively out there and breeding, which is great.

If you guys like, you, obviously like Australian English, but I've had quite a few people asking me about TV shows and movies. If you like Australian film and animals, go and check out oddball...

Oddball is the movie made about that story of the Maremmas with the Penguin Protection.

In Warrnambool. Yeah. And you get to see a lot of the coast and some colourful characters, it's great. Yeah. So, did they do that on French Island, too? Is that where...?

Yeah. Some of them have been released on French Island and Churchill Island, they're two islands in western Port Bay, which, for the geography, anybody who is interested in Victorian geography. Melbourne The city is at the top of Port Phillip Bay and there's a bay right next door to it, separated by a peninsula, the Mornington Peninsula called Western Port Bay, which is ironic given that it's on the eastern side of Port Phillip.

But it was named first and it was- And there are three islands. There's one Phillip Island that effectively closes the bay off, there are two, one narrow and one quite wide channel into and out of the bay. And there are- There's a large island in the middle of the Bay, French island, and there's a little island called Churchill Island that is just off Phillip Island that is a conservation place.

It's a historic farm as well as the conservation areas, so they've released them in both Churchill and French islands, and those populations are being monitored and apparently are doing well. So, it's good.

It's funny, as sort of a side note. We used to go to Phillip Island quite a lot because mum, I don't know if you two, mum was doing fieldwork...

Yeah, we both were.

...Both did. So, you were both obviously zoologists at Melbourne University and your respective supervisors obviously had work, were doing work along the coast, the marine biologists. And you guys have worked down there, mum was looking at barnacles, you were looking at mussels.

Mussels. Yeah, on the rocky shores on Phillip Island...

Is that where you proposed? You proposed down...

On Berry's Beach. Yes.

We didn't get that. Where was it? Berry's beach?

Berry's beach? Look at that. I've got that on record now. I'll remember long after you're gone, I'll be able to...

You will, yeah. Well, you know, my ashes will be scattered on Berry's Beach if you follow what's written in my will, so.

I'm not going to read that.

No. Of course not.

I just want the house.

Just give me the money.

But, yeah, I remember thinking for years that the place was called Phillabisland.

Phillabisland?

I never realised like, it's funny thinking about that linguistically as a child because it was before I could read or write. And, you know, you're just going off what you can hear. And so, it was for ages, I remember thinking, it's one-word Phillibisland, Phillibisland, Bisland. And then only later you're like, oh shit, it's Phillip Island.

Yes, it's an island named after Mr Phillip.

Yeah, there are so many of those- I keep thinking that because of Noah obviously learning two languages at the moment both English and Portuguese, my son Noah, and always thinking about some of the words, the sentences he constructs, especially now that he's mixing languages, he- I wonder if he realises the word like "wanna" is actually "want to" because he probably never hears, "want to", "Do you want to do this?" He just hears "wanna".

And so, he'll chunk things. He'll say, I wanna tire isso, which means "I wanna" in English, "I want to" and "tire isso", he'll be pointing to his jacket in Portuguese, saying, "take off this, take this jacket off". I wanna tire isso or isso. And I'll be like, it's funny because I don't even think about it anymore, I just hear it and get the message.

And I'm like, oh shit, okay, so he's chunking, "I wanna", and then he just says, "tire isso or tire isso" at the end and just puts them together. And so, it would be so- It's so interesting what's going on linguistically in terms of him working out what words are, where they start and finish, how they interact...?

Yeah. Well, we all do that. We all do that.

Yeah.

We learn to speak the language before we understand passing the language into- We understand syllables, but we don't understand parsing those syllables into words because we just put them together into a sentence.

Do you have any of those? Do you have any of those where you thought that the multiple words...?

I probably do, but I can't remember them now. But I remember the one you talked about, Noah, where he used to say, "it scumming".

Yeah.

And then he'd drop the kids and he'd just say, "scumming". Oh, he would say, "dada scumming or dada scoing".

...Was the word, or "scoing".

Yeah, so he contracted "is" onto the verb in front of it, right, instead of onto the pronoun. So, "scumming".

"Scumming".

Yeah, that was hilarious. I remember that all the time.

Yeah. He's dropped it now, though, so he now speaks properly. No.

Yeah, it is interesting, and for a while now, he's talked in the- He talks in the first and the third person, so he will say, "I wanna", then I wonder, I haven't analysed it enough, but I wonder if in certain situations, he's just used to using "Noah". So, he'll refer to himself as "Noah", "Noah want to go outside"...

Yeah.

...Or Noah, want to go dada carro. carro, like in dad's car.

Yeah, dad's car.

Yeah. And so, it's really funny because he'll switch between the two. And you were saying that your granddaughter, my niece Isabelle, for a long time was saying...

She used the second person...

When she met her because she would hear someone say to her, do you want to go outside? And she would say, "you want to go outside" or whatever, or "you want to..."

Yeah. She meant herself. Yeah. And that was interesting because she had exceptionally developed language skills very early on. She was speaking sentences at one and people go, you mean one and a half? And I said, no at one.

Well, wasn't there- There was a time where she was wandering around at our house and she must have been about one year old. And I said to her, hey, Izzy, you know, being a smart arse, can you say "ultrasound"?

Yeah.

And I remember she turned around and said, "Ultrasound", you're like, you bitch.

Well, that was when- that was- The ultrasound was the day that you had got the ultrasound when Noah was, you know, Noah was, you know, in utero. So, you can date that, she was less than 18 months old. And so, yeah, but because her language was so well developed and that distinction between first person, second person and third person is a much later development than just sentence construction and parenting and so on.

But so she could understand that you meant her when I was saying it or her mother was saying it or her father. But so, she...

As in the word "you" meant...

Yeah. You could just say she just used it to repeat it back.

Yeah.

And so, and very, very few other children do it...

She's kind of like a Jedi, right? It was like, "you want food..."

Yeah, exactly. Yeah, exactly. "You want to go outside." No, I don't.

No, no. you want to.

Yeah. And so, it's that really interesting thing of language development where she had the language skills to speak in sentences before that next stage, whereas most children develop those simultaneously. So, Noah, will never say that.

Yeah.

Because he can understand that he either refers to himself, by the pronoun or by his name.

Yeah.

And so, because he's, you know, now two and a half, he's worked out that this is how you, you know, you deal with the world.

Well, it's been really interesting. I had some notes on my phone. I'll see if I can pull them out because I was sort of following his language development for a while and taking notes down and sort of seeing what's he learnt to say. So, like, what have I got here? So, "dada scumming. Dada scoing". That was March this year.

And then in June, it was the possessive S he started using, "Noah's car. It's broken, sbroken". He was saying, "sbroken" and saying, yeah, "broken pequeno, little broken". Later that month, he was saying, "Bye bye monster truck. See you again." He started playing with toys and talking to them, so he was narrating things and started using "I" instead of "Noah".

And yeah, he started using Phrasal verbs, I was like, far out. He's already saying things like, "I put it on". And I was like, holy crap, even- Not even that, it's a phrasal verb, that needs to be split, right. So, you can't say, "I put on it", you have to say, "I put it" and then "on", you have to put the object between the two.

Yeah, the subject in that case is there, but the- Well, sorry the object is there, the subject is assumed. You know, "I put it on me" is the...

Yeah. Well, that's it. So, I was just blown away by some of these things. And then I think later that month, again in June, he was starting to mix things. So, he would say, like, "I face a snake." I made a snake out of Play-Doh. "I face a snake", and "I fall off", again, phrasal verbs.

And then inverted questions later that month, "is Nana coming today?" I was like, holy crap. Like, it's probably not as mind blowing as it feels because I- For me, teaching people learning a second language, it's always like, those are advanced things that, you know, you learn in order to get pretty fluent.

But he's probably not so much learning, okay, I'm learning how to use Phrasal verbs. He's learning how to use a phrase, and then he just repeats that phrase, you know, all the time and doesn't actually realise, oh, I'm using an inverted question or I'm using a phrasal verbs. He's just like...

...That's how we learn a language. We learn the sophistication of the language by just copying it. And then we'll- Years later, we'll actually unpack the syntax and the grammar to work out how to apply those rules to another context.

If we ever to do that, right?

Yeah, yeah. Exactly.

It took me learning a foreign language to do that with English.

...Not consciously. But yeah, it's a funny one.

Yeah. Anyway, sorry, let's move on...

Nah, animals. You want squirrels or drills?

Go for the squirrel one. Tell me about that, dad. I sent it to you, but I...

The squirrel one's bizarre.

Got it.

This is one of these ones of not the story's bizarre, but the way the story is told is bizarre. This is- The headline is, squirrels have human like personality traits...

Okay.

Their endeth the science.

Endeth?

Yes, the ends the science, everything after that is just Pulp Fiction. Now they're quoting, and I'm sure it's accurate, but it's- We never actually get to understand what the study was and so on. But we're getting told that- This is the sort of stuff that drives me nuts as an ex-animal biologist. According- I gotta go, here we go. The data collected over a three-year period led analysts- Sorry.

To conclude that the bolder and more active squirrels covered more ground and were more successful in amassing resources such as food than their more shy and less active counterparts. No shit, Sherlock. You needed three years to work out that those that went out and looked for food more got more food.

And then the more aggressive squirrels also had greater access to perches, such as rocks, the study revealed, providing better- No shit Sherlock...

There must be...

...Science that sits behind this, but that's the story that gets told. And that's the problem we've had, we've talked about this a lot of when science is told- Yeah, when science is communicated in the, you know, the mainstream media, it gets dumbed down to tell a sexy story. Rather than saying, hey, there's a really cool scientific design that went on in order for us to establish this.

We just get the no shit Sherlock result, and everybody goes, why did I spend money...? How come these scientists got hundreds of thousands of dollars to go and research something that I could have told them without even doing anything?

We had an example of that in Sulawesi. So, for you, Indonesians, you should be really happy with your- Trying to write this at the same time as... (both talking)

...You can't do it.

Yeah, no. I can't talk and type at the same time, especially different things.

Unless you're- If you're Y chromosomally absent, you can do it.

You should be really, really proud of your rodent diversity, the rats that you have. And I've actually just found here. So, when I was in Sulawesi in 2012, my supervisor- I think it was about that time. Yeah, it was. 2012. It was on that trip, he discovered Paucidentomys vermidax, which is effectively a rat with a really long snout at the front of it. It kind of looks like...

Worm-like nose that...

Yeah. And so, it was a rat that had a very, very long, pointy nose, and it was really interesting because it had no molars. It just has these front teeth, sharp rodent teeth at the very front of its mouth for cutting up worms. And so, it effectively just hunts worms, chops them up and swallows them down and doesn't chew on in terms of...

...Chew things that don't have hard body parts. Yeah.

It doesn't. Yeah. And so, it's lost all of its molar teeth. And so, it was the only rat that's ever been found that doesn't have any molar teeth, it just has effectively the two pairs of teeth...

...At the front and that's it.

Yeah, on this long snout. But the story was that effectively when this rat was found and my supervisor described it to science and created this, you know, it was a new genus and a new species of rat. And it was cool because of the molars and everything, and that it was just nothing had ever been found like it.

All the news stories were worm sucking rat or, you know, toothless rat, you know. And so, it was really funny how they had to turn it into this really hyper, you know, big, sexy story, and in order to get people to click on it.

But yeah, it looks like Paucidentomys has been turned into a stamp as of 2019, and it's the photo that my supervisor took. Yeah. It looks like it's called tikus ompong, I think tikus means "rat" in Indonesian and ompong(toothless), I'm not sure what that would mean. I'd need my Indonesian... (both talking)

...dictionary. We used to have one...

But very cool.

...No, it's not there. I could look it up online, but it would take too long.

Yeah, but that's just really cool to see it as a stamp. So, it's cool to see Indonesia's supporting or celebrating its wildlife. Unfortunately, the rats dead on the stamp. So, yeah, that was the other cool thing with when you catch all these animals, they're caught in traps, so they come to you dead, or they're caught by people who kill them and then bring them to the camp for you to look at.

And so, my supervisor- Oh, ompong means "toothless". My supervisor would have to like, get this moss and nice rocks and try and situate...

Oh, yeah. Of course, you do.

...Look like it was alive. Like he would lick his finger and put it on the eye...

It's not dead.

Yeah.

It's just pining for the fields.

Well, he was trying to take a photo of it for science, right. So, you didn't just have this stuffed animal, because a lot of the issues that we have with being scientists who work with animals that have been caught in the wild in the past, you know, working out of museums on specimens, is a lot of the specimens don't have photos. And so, you have no idea of what it actually looked like.

It's been stuffed or skinned by someone later on, so a lot of the rodents in Australia, for instance, that went extinct in the 1800s, we don't actually know what they look like because no one took a photo of them. They just have- We just have these weird looking stuffed exhibits.

And I think that's something that people need to understand about taxidermy is that the skeleton and the skin are separated.

Yeah.

And then the skin gets built up with basically wire and newspaper and paper maché bodies underneath...

And I think...

...It was wrapped around it.

...It was treated with chemicals to prevent bugs and other insects and moths.

...But the...

But that would bleach it.

...Ends up looking like is what the taxidermist- Because often the taxidermist just gets the body...

He's never seen it.

...And often just gets the skin and, you know, never actually even saw the skeleton, so.

Well, if you want to get scared, go online and type in, you know, "taxidermy gone wrong". And I'm sure you're going to see a lot of animals that are like turned into monstrosities later on after they've been taxidermied. So, the last story here was the drill invention that fast tracks creation of tree hollows for wildlife displaced by fires, which was really cool. It's one of those things, so- I guess before I go on a rant about it.

An innovative drilling technique that fast tracks the creation of hollows in tree trunks aims to create a million homes for wildlife displaced by Black Summer bushfires two years ago. So, this is circling back to the very first episode of the Goss' the start of 2019.

As catastrophic inferno has destroyed more than 5.5 million hectares of wildlife habitat, millions of animals that relied on tree hollows for shelter and breeding became displaced and vulnerable to prey. Using a new drilling technique called the Hollow Hog that speeds up the natural hollow development process. These hollows are going to be made, which normally take if they're done naturally 70 years or more.

And effectively, a hollow inside a living tree is made when a branch falls off and the remainder of the branch kind of rots out and leaves an entrance into the wood. And then I think a lot of the time animals end up getting in there and making it an actual hollow, right. Yeah, what we would call a hollow where they can then use it and live in. And the cool thing is, obviously there's a lot of turnover.

So, when you have these hollows, animals tend to only really occupy them for a season, you know, like, say, birds that are nesting in a certain hollow. And so, you can end up with different animals using it every single year, just rotating through whether it's mammals, birds, goannas.

Yeah, so they're really, really important in Australia for a lot of the wildlife. I think I was reading here that 15% of Australia's wildlife, including 300 species of birds, reptiles and mammals, rely on hollows for shelter. Animals prefer them because of their small entrances, which allow them to tightly squeeze through and avoid threats from larger predators.

And what the hollow hog allows us to do is to rapidly form a hollow in a tree and sometimes multiple holes in a tree and speed up the natural process. So, the hollow hog is effectively a drill, and they go up to the tree and just drill a hole in there.

I think he was saying the width of a finger or so, maybe a bit bigger, and then it will gradually get bigger and bigger as the tree develops and grows. Or it'll allow the animal to be able to sort of get entrance...

It'll allow small animals to get in and start...

Hollowing them out.

...Hollowing it out.

And so, it was cool. I think the guy here- Where is his name? Matt Stephens, who is the inventor of the Hollow Hog from Transport for New South Wales environment. So, he's the officer there. He was saying that he's- We've had uptake by some lorikeets, bush rats and Antechinus, so marsupial mice, and in some cases within 20 minutes of installing a hollow a tree creeper flew around and inspected it.

So, that quickly they had other animals, other birds looking at those hollows. So, yeah, why is this important, dad, in sort of the modern Australia?

Well, I think you've just said it, but you know, we have such a high proportion of our wildlife that rely on tree hollows, and we can do that in Australia because we have traditionally eucalypt forests, which are long lived. But eucalypt branches are brittle, so long-lived trees have lots of branches that have broken off them. Whereas coniferous forests are not like that. The coniferous forest branches tend to survive in conifer forests...

Like pine trees.

...Pine trees and so on. So, tree hollows are not as common. They are still used, but not as common as they are in Australia.

This is one of those tips, right, to say just quickly, if you guys go camping, don't camp under a eucalyptus tree.

Don't camp under a large eucalypt... (both talking).

You'll often see that, too. There's a- There's that red gum right near...

River red gums, yeah.

The river red gum near Noah's day-care, and you'll walk past there and there are just huge logs under it. Because it's been fenced off and it's obviously been there for a long time, there's no fire that's gone through. And so, all the branches that have fallen off this thing...

That's actually quite a famous tree on the Bellarine peninsula, I think it's been aged about 600 years, so.

I think it was 200 and something. But yeah, it was before we were colonised, it's crazy to think about it.

Yeah, so, those big branches fall off and small branches fall off, and ironically, they don't necessarily fall off in high winds and storms. So, you know, you might have had a really windy period a week or two or three ago and then it'll have weakened things. But eventually the branch will fall off and often it occurs at night because you get the change in temperature, and so you get the contraction of things and really cold nights.

If there are little hollows and cracks and things, they'll fill with water. It doesn't even have to be raining, with condensation that'll turn to ice, and of course, ice expands. And so, you get these branches falling off in the middle of night rather than in the wind during the day, so.

Well, it's interesting, it's probably been selected for as well because it builds up fuel on the forest floor that can then burn during bushfires. Because a lot of Australia's trees require being burnt by bushfires to sort of instigate to encourage reproduction rate, for them to release their seeds.

They often need to either to release the seed or to germinate the seed or- And often they're combined to create space around them so that the young sapling can actually grow up. Because these bigger trees have got such a huge coverage of their canopy that, you know, very little sunlight will get through and they're sucking up most of the water.

Whereas if you get a fire that rushes through and kills off the canopy, it doesn't even have to kill the tree, it just has to wipe out the canopy for a while until the tree re-grows it. But then you've got this big space with a lot of sunlight that can get to it. The ash that gets created in the fire creates fertiliser on the soil. So, it's this this whole multifaceted cycle of being able to germinate young trees.

So, a lot of Australia's forests require it for re-germination. Ironically, river red gums that's not true for, what river red gums require is flooding. Hence being a riverside tree, they require the every 5, 10, 20 years there'll be a major flood, and that flooding, the water that sits over the area for a while will soak into the ground and the seed will absorb water and then it'll germinate.

So, it doesn't need fire, it needs to be wet in order to germinate. So...

By the way, anyone who's watching the video, you'll be able to see eucalyptus...

Eucalyptus in the background.

So, that's- These are...

The world's tallest hardwood tree.

It is really interesting. It's one of those things that is very- How would you explain it? If I ever moved away from Australia, I think this is one of the big things that I would miss, these trees. I was trying to explain this to Kel the other day.

I'm like, do you have anything from Brazil where you were living there like animals or trees or environmental features that you just couldn't take with you, obviously, when you came to Australia and that aren't here? You know, like, I would miss hearing magpies call and plovers calling and, you know, the currawongs and a lot of these trees.

But, yeah, it is interesting. So, you can see in your background that these trees have these, you know, lots of these abundant green leaves. They have this stringy bark that again is probably associated with falling off, covering the ground, creating fuel that can be then burnt by fires, but also preventing other trees from growing on the floor.

And then also they drop a lot of these branches, and a big thing is that the oils in the leaves are highly flammable. And it's I think it's to encourage fire, right. But also, to allow fire to burn fast and hard...

It's really hot fire. So, it burns really quickly, and it doesn't sit there for hours, burning through and killing the...

Entire tree. Yeah. Yeah. So, you end up with...

...Lose leaves, you can regrow those. But you can't regrow bark once it's dead.

Well, and this is one of those interesting things with these eucalypts. I don't know if you could just chop one down in terms of like, leave a bit of the trunk and it would still survive. But when I was living across the road from Royal Park, when I was in, would have been on- What's that road there? Is it...? Yeah. Flemington Road across from the Royal Children's Hospital in Melbourne.

There's a bunch of really big eucalypts down there and they just chop the tops off them effectively because they were obviously getting too big, and the branches were starting to tangle with the electricity lines or the tram lines. And I thought, fuck me, they've just killed these trees and just left these trunks here. Why wouldn't you just, you know, just trim them a bit?

But within three or four months, they had afros effectively on the top of them, like they had so much foliage that had grown, spurted out from the trunk that it had completely regrown, and you would turn into a bush, you know, like, oh, wow. So, this is what happens when they get burnt or they get chopped down, they just sprout out everything again, they don't actually die.

Yeah, they're called epicormic buds, these dormant buds that are actually in the trunks of the tree. And when the leaves that are above them, they get either burnt or chopped off or whatever, then the hormone balance in the tree gets recirculated, changes and those dormant buds start to crop up.

And so, you've got some of the really tall trees like the eucalypts that are behind me here are less likely to do that, although they need major damage.

Yeah.

But if you cut the tree completely down and just left the trunk, then the epicormic buds are quite high up on the trunk. Whereas there are other species of eucalypts in- Mallee eucalypts, for instance, that occur in much drier areas where you can cut the tree down to ground level and those epicormic buds will pop up from the root ball.

Well, some of it is cool, right, where the tree will fall down on its side and then...

They all just grow up.

...They all grow up out of the trunk, and it turns into...

...Like these little mini tree's...

...Coming out of the one...

...Growing out of one branch.

Yeah, it's just crazy, isn't it?

Yeah.

Anyway, I don't think there's much else to mention there, I guess, yeah, it's just really cool. I thought for ages, why aren't people just going around with drills and drilling holes into the side of these trees? I think a big issue they had in the past was that the techniques they use could quite often ring bark the tree, so remove effectively...

Causing disease. Yeah.

...Causing disease or removing the part, if you trim the bark right around the ring of the tree...

Yeah. Well, you can't do that.

...The water can't go up the tree and...

The nutrients can't go down. So, yeah.

Yeah, exactly. So, you end up with issues like that. But I've thought for so long, why the hell aren't people just artificially creating hollows in a lot of these trees? And I mean, I imagine it's probably pretty laborious and requires a lot of work. But yeah, very cool that these guys want to do, I think a million, yeah, they want to do a million holes in a million trees. Well, or less in the next few years, which is really cool.

And it could be used overseas, it could be used all throughout Australia, which is probably going to become more and more important, the more that climate change affects our environment, and we have more bushfires killing these trees.

And that's the issue. These trees take hundreds of years quite often to get fully developed.

And that's the thing with old growth forests that you need a tree big enough to have a branch big enough to fall off to create a hole. And then, as this article has suggested, it can take up to 70 years or more for that hole to become usable by animals.

So, we're talking about trees that are hundreds of years old that have hollows in them, whereas now if we can artificially create some, we can create them in younger trees, which means that, you know, we can start to get establish more diverse animal communities in places that are not old growth, which is a good thing.

And something we did forget to mention is the fact that it's different from just putting boxes, hollow boxes onto trees because these are not protected like hollows are within the tree. So, the- Like a burrow in the ground, the climate within a hollow that is in a tree is actually kind of pretty regular.

It's maintained, it doesn't go up and down in terms of temperature, or humidity as much as, say, a box on the outside of the tree that is exposed to sunlight and to rain and the weather a lot more. So, that's why that hollow boxes may not necessarily be an answer for every single species, whereas if you can create hollows in trees, it's probably going to help a lot more species.

And hollow boxes are expensive and time consuming to manufacture and hang, whereas if you can just go and drill a hole, which will take a couple of minutes and move on, it's much more effective. Yes, it'll take a bit longer, but it'll be a more effective solution, as you say.

Awesome. Well, thanks for joining us, guys, and we'll see you next time.

Thanks, everyone. Bye.

Alrighty, you mob. Thank you so much for listening to or watching this episode of The Goss'. If you would like to watch the video if you're currently listening to it and not watching it, you can do so on the Aussie English Channel on YouTube. You'll be able to subscribe to that, just search "Aussie English" on YouTube.

And if you are watching this and not listening to it, you can check this episode out also on the Aussie English podcast, which you can find via my free Aussie English podcast application on both Android and iPhone. You can download that for free, or you can find it via any other good podcast app that you've got on your phone. Spotify, podcast from iTunes, Stitcher, whatever it is.

I'm your host, Pete. Thank you so much for joining me. I hope you have a ripper of a day, and I will see you next time. Peace!

Listen & Read with the Premium Podcast Player

Get more out of every episode!

Premium Podcast members get access to...

- All 900+ podcast episodes including member-only episodes

- Member-only episode video lessons

- Downloadable transcript PDFs & audio files for every episode

Recent Episodes:

AE 1299 – Pete’s 2c: Do You Ring, Call, or Dial Someone on the Phone in Australia?

AE 1298 – Learn English with a Short Story: Day at the Beach

AE 1297 – The Goss: How ‘Dropping In’ Culture Has Changed in Australia

AE 1296 – The Goss: Gorilla Glasses & Dad’s Crazy Zoo Stories – MEMBERS ONLY

AE 1295 – The Goss: Australia’s Most & Least Ethical Jobs

AE 1294 – The Goss: Australia Just Had the Best Aurora in 500 Years!

AE 1293 – The Goss: Should Aussie Schools Ban Homework?

AE 1292 – How Aussie Do Asian Australians Feel? r_AskAnAustralian

Share

Join my 5-Day FREE English Course!

Complete this 5-day course and learn how to study effectively with podcasts in order to level up your English quickly whilst having fun!

Join my 5-Day FREE English Course!

Complete this 5-day course and learn how to study effectively with podcasts in order to level up your English quickly whilst having fun!

Want to improve a specific area of your English quickly and enjoyably?

Check out my series of Aussie English Courses.

English pronunciation, use of phrasal verbs, spoken English, and listening skills!

Have you got the Aussie English app?

Listen to all your favourite episodes of the Aussie English Podcast on the official AE app.

Download it for FREE below!

Want to improve a specific area of your English quickly and enjoyably?

Check out my series of Aussie English Courses.

English pronunciation, use of phrasal verbs, spoken English, and listening skills!

Leave a comment below & practice your English!

Responses