AE 1163 - INTERVIEW

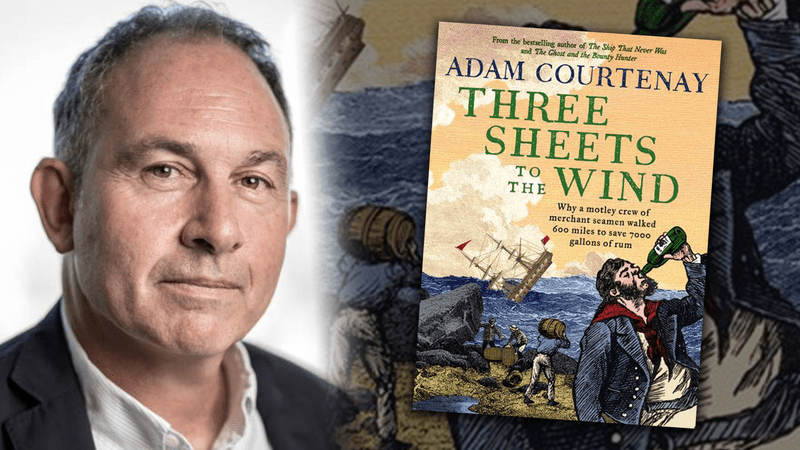

Three Sheets to the Wind with Adam Courtenay

Learn Australian English in each of these episodes of the Aussie English Podcast.

In these Aussie English Interview episodes, I get to chin-wag with different people in and out of Australia!

In today's episode...

Let’s welcome back the brilliant bestselling author of The Ship that Never Was, Adam Courtenay!

Adam is back on the podcast as he talks about his latest book Three Sheets to the Wind.

It’s about a band of merchant seamen who had to walk hundreds of miles across Sydney to save 7000 gallons of rum.

But it’s a beautiful tale about brave men and how language barriers are overcome when one needs help.

Imagine English-speaking men who communicated with different indigenous tribes, trying to get where they need to be.

And finally, you also get a trip down historic Australia! It’s a truly great read!

Let me know what you think about this episode! Drop me a line at pete@aussieenglish.com.au

** Want to wear the kookaburra shirt? **

Get yours here at https://aussieenglish.com.au/shirt

Improve your listening skills today – listen, play, & pause this episode – and start speaking like a native English speaker!

Listen to the convo!

Listen to today's episode!

This is the FREE podcast player. You can fast-forward and rewind easily as well as slow down or speed up the audio to suit your level.

If you’d like to use the Premium Podcast Player as well as get the downloadable transcripts, audio files, and videos for episodes, you can get instant access by joining the Premium Podcast membership here.

Listen to today's episode!

Use the Premium Podcast Player below to listen and read at the same time.

You can fast-forward and rewind easily as well as slow down or speed up the audio to suit your level.

Transcript of AE 1163: Interview: One of Australia's Craziest Survival Stories with Adam Courtenay

G'day, you mob. How's it going? Welcome to this episode of Aussie English, the number one place for anyone and everyone wanting to learn Australian English. Guys, today I have an amazing interview episode for you. I've got an amazing guest, Adam Courtenay, who is a Sydney based writer and journalist.

He's had a long career being a journalist in the UK and Australia, writing for papers like the Financial Times, the Sydney Times and The Age, and more recently has turned his love of Australian history and stories into five books, including "The Ship That Never Was" and "The Ghost and the Bounty Hunter". And we talk about that book on episode 663. Go check that out if you haven't already.

And more recently, he has published the book "Three Sheets to the Wind". So, today we talk about that and this incredible story of a group of merchant seamen who walked 1,000 kilometres to save 7,000 gallons of rum. So, guys, without any further ado, I give you Adam Courtenay.

Adam, how are you going?

Really, really well. Thanks, Pete. Peter, it's great to be back after two years or a year or two. Two years, I think. Yeah...

Yeah, you were- I have it up here. It was episode 663. So, that was when we were talking about your previous book, "The Ghost and the Bounty Hunter", which was incredible. Go check that out, guys. But that was, yeah, I think that was about two and a half years ago.

So, how have you been in the meantime? How was COVID? You were obviously very productive.

Well, I had to be productive. I guess it was a good time for writers in a way. In a way it was good because what else did I have to do? The thing is, I'm also a journalist and the work really did dry up. There was just no advertising for obviously magazines. I mean, it's not- It didn't completely dry up. There were still journalism opportunities. But there were long stretches of weeks and weeks where I thought, well, here's the time.

I might as well make the best of it. And I think many, many creative people did. And I know a lot of people who did their so-called pet projects during the COVID period. So, it had its good side. The bad side was I needed to get out and see many of the things that I was writing about.

Yeah.

Luckily I'd done this before the COVID problem and I'd done about half of what I'd seen. And so, in the end, I finally got to see all the other things that I needed to, but it was touch and go before publication. It was really weeks before publication that I got to see some of the things I needed to write about and get them all done.

Oh, brilliant. So, yeah, I guess the good news is and this came out last month, actually two months ago now...

...Month- 16th of June. What's that?

Yeah. One and a half... (both talking) ...I'll hold it in front of me, but "Three Sheets to the Wind". Can you tell me in a nutshell what the story is about and what made you decide to write the book?

Yeah, look, it's about- It's two things. Firstly, just to give you a bit of background. I got the idea. It's... (Inaudible) ...pretends that one gets the idea out of thin air. I got the idea from a book called "From the Edge", which was done by a well-known Sydney academic whose name I just can't remember at the moment. It'll come to me. McKenna. Professor McKenna. He's the head of history.

And he'd done a book "From The Edge", which was a short sort of story, a chapter about the Sydney Cove and I saw it in an ABC article about 2017 or 2018. That's really interesting. I'll just put a check on that. And then I spoke to McKenna and I said, "well, do you think this is a- This could be a popular history type story? Do you think there's enough in it?" And he said, "No". That's why I only did a chapter on it.

And I think he was right. He wrote only about the great walk that these men had done. Let's start with what the book's about. It's about- It's essentially about rum. It's about a great voyage from Calcutta to Sydney to provide 7,000 gallons of rum to Sydney, which was, let's be particularly honest, it was totally addicted to rum.

It's all they had. It was their only form of enjoyment was the alcohol, but it's also became the only form of payment. It became so ubiquitous that it became so precious that these people from the Sydney Cove, which was coming from Calcutta, knew that they'd get a- Fetch a brilliant price if they could get the rum all the way to Sydney.

So, here starts a story of 50-something men, mostly lascars, mostly Indian sailors coming from Calcutta, having to go across the Indian Ocean through down to Western Australia. And on their way, of course, they sprung a leak as they were wont to do in those days. And the lascars basically for I think a month or on and off were having to bail and this poor Sydney Cove...

It slowly made its way- It went through terrible weather down in the Southern Ocean and just sort of limped its way up just past Tasmania before it gave up the ghost, so to speak, and found itself on Preservation Ireland. So, there was 50 something men, 5 had died, 5 lascars died on the way because the bailing was just too much for them.

They're poorly paid, they're poorly fed. And so, 17 men or at this little Preservation Island, tiny island at the top of- In the Furnaux Group, at the top of Tasmania, and they take a long boat and 17 of them decide they've got to get to Sydney, so they want to sail to Sydney.

And in doing so they became the first people to cross Bass Strait because we didn't know at that time that there was actually a strait between Tasmania, Van Diemen's Land as it was known then and the mainland, Australia or New Holland as it was called.

So, they cross Bass Strait thinking they thought they were going upper coast, they were actually going to the southern coast of Australia. So, they find themselves marooned or shipwrecked twice in a month because the Torres Strait, as we all know, isn't going to give them any quarter and they get washed up on Nine Mile Beach in Victoria. And this is where the Great Trek begins. This is where Professor McKenna started pretty mu- Oh, no.

He did the book- He did his book- The sailing trip. But the big part of his book is this incredible trek. For these men to try and save their- To get to Sydney, they couldn't sail anymore, obviously the boat was- The long boat was wrecked.

They had to walk 600 miles and had to walk through Aboriginal lands. And this is- The most important part of the story is about the trek, but it's about many, many other things as well. It's about the value of rum, it's about how rum corrupted a society.

Why were they travelling to- They had 600 miles to go and the question is, was it all worth it? Was it worth going all the way to Sydney? Was Sydney worth it? And that's at the crux of the book, Peter.

Yeah, it's one of those stories, isn't it, that feels like the only sort of equivalent to how they probably viewed things at the time would be like having a colony on Mars today and you having a ship going out to Mars and it lands on the opposite side of Mars to the colony. Right? And then you...

Why didn't I put that in the book? You should have written that. That's a brilliant analogy. No, very, very good.

But I mean, that's how I try and I guess imagine- Whenever I've read about Australian history, especially that period in the early colony where it was on the other side of the planet. But today for the average person living on planet Earth, you know, it kind of feels like the other side of the planet isn't that far away anymore and it's pretty civilised, right.

But for them at the time they would have- The colony was only, what, 10 years old, maybe even younger, right? 8 years old?

8 years old.

Yeah. So, this was 1796, wasn't it?

1796. Yeah. Well, actually, they started their voyage in late 1796 and got- The second shipwreck when they finally got on Australian or mainland soil was March, if I remember correctly Middlemarch, around about- Yeah, no. Beginning of March 1797.

So, yeah, Australian- Sydney was the only so called quote unquote, I don't want to use this word "civilised", settled place, settled by Europeans. The only settled place in Australia by Europeans, it was the only place for them to go. And of course when they get to Nine Mile Beach, it's this long beach stretching for miles. You can't see one end to the other. And they didn't- They thought, what- Are there lions and tigers here?

Are there crocodiles? And of course, every person- Every native person in those days was considered- Any first nations people, from any country this is, were all considered savages. So, the first thing on their mind was this sort of rot that would always come through at that time. But it was part of history. They thought they would be cannibalised, of course, and they'd be head hunted.

If they're not cannibalised, they'd be head hunted. Of course, that was totally and utterly false. And this main man, the super cargo, the man who held the cargo, who became the sort of leader, the de facto leader of the 17 crossing along the south was William Clark.

And William Clark was a Scotsman. He didn't know what to think. But I think what I like about Clark is he sort of didn't err on the side of these are savages, barbarians type thing. Let's just- We're in the minority here. We're crossing- He understood very clearly that they were crossing other people's land. It was not terra nullius. Even he didn't accept that. And he knew very clearly that he was entering into other people's land.

And he must act with great diplomacy, which is what he did.

He seemed to have a really interesting fight within himself. Right? Because it sounded like from what you wrote that he was kind of somewhat bigoted towards them. But then the more he went through the trek and got to understand them a little bit, he was like, oh, wait, you know, these people deserve my respect and our lives depend on these people effectively. Right?

Like, it's...

Exactly.

It's interesting to see how many people back then had that- That maybe they had those bigoted expectations from before they even came in contact with any sort of indigenous people anywhere.

It was just inherent and in their mindsets and...

But then had their minds opened, right, as soon as they did get to meet them and...

That was a wonderful- This is really what I think is the most wonderful thing about this. I don't like the word reconciliation. I just think it's conciliation. It's too- It's how- What I found interesting was it's how two people who are so culturally foreign to each other just find the humanity in each other and realise that it's-

The First Nations people that they met, the first people they met were the Gunaikurnai. And they just sort of was just curious, they just said, who are these- And remember of course they weren't all white men, there was- Actually white men were in the minority, but there was 5 white men and 12 lascars in this group of 17. And so, the Aboriginal people, the First Nations people who would have met them would have just been curious.

This motley stinking crew, they found that they probably- But they treated them very cordially. They were just- They inspected them. They probably wanted to see if they were men, they didn't know. They probably checked if they were- Had been- Had their front tooth knocked out. I don't know whether one or two of them had, maybe they did. That was the initiation ceremony.

But they- It didn't matter that they- He didn't realise of course that they used whale oil or fish oil to ward off mosquitoes, an actual insect repellent, and they found that extremely repulsive. They found- Clark says, he said, these are the most repulsive people I've ever met. But as he goes along and the days turn into weeks, it just seems like that sort of- It's just-

It doesn't even register anymore, whether they look different to him or he just he sees them as a sign of- And they come to him cordially, most along the southern coast. And when he gets up to places like Eden, they're even more cordial. They're giving him fish. They're showing him the ways. We think- We're pretty sure- Because he says we caught some fish. How did he catch fish? He must have been given some fishing gear.

And he says he gets fruits and nuts. They showed him the way through. They took him, they canoed him across a river. Now he's calling them old friends. There's no talk of them being ugly or different. Or he's saying these are my old friends, and they always said to pop up at all the right times. They come to a raging river and there's the first nations peoples ready to take them across in canoes.

So, it's this really nice story of people who don't really get each other but think, well, okay, they realise that Clark and his entourage are just trying to get across country. They're not taking from country, they're not stealing, they're not abusing it in any way. They just want to get across. They don't really want them there because they don't want foreigners. Like it's a natural response.

We don't quite know what to do with them, so let's help them on their passage through. It seems to be the smartest thing to do. And then the next- They will come to another tribe and hopefully- Of course, the news would have been relayed all the way up the coast that these men were coming. It's absolutely 100% sure. And firstly, I mean, let's go through the various different responses of each tribe perhaps, might be interesting.

Yeah, go for it.

Yeah. If you want. I mean...

Absolutely.

We talked about the Gunaikurnai. I think that what they showed was they were very- They were around the Mallacoota area. You'd know that being a Victorian.

Yep. This is... (both talking).

Yep, yep. The Gippsland area. The Gunaikurnai of are from that area. And they were very inquisitive and they were very, very friendly. They got- Once they rounded the coast coming towards today's New South Wales, they met the Thaua people and that was around Twofold Bay around Eden, the Pambula River and Merimbula. That's the sort of area that these people lived in, and that's the area of-

These are the people that I think gave them food, showed them the country. They were probably the friendliest of all the people they came across. And gave them, I think fishing gear. Showed them, I think their fish traps and their eel traps, allowed them to partake. I think they were supervised. So, during that- It was a very nice time when they came across the Thaua people.

It was a beautiful country. They called it the Emerald Coast, I think, down there. I've been down to Twofold Bay and Eden and it's just- The countryside around there is beautiful. So, I can imagine they actually had quite an enjoyable trip, even though of course it was very hard going.

Then they came to the Djiringanj and that's around Wallagoot Lake, Bega River. They were more hostile, more suspicious. It's an interesting story that I tell in there about how the Djiringanj and please, any First Nations person listening to this please forgive my pronunciation, it's probably not very good.

Around Mount Dromedary- And the interesting story is that they saw Cook as he came up the coast and saw him as a kind of predator. They saw him as a pelican. And one of the oldest there told me that they saw Cook as a predator, as a pelican, and they only see pelicans as predators who steal fish. So, they never were all that crazy about white people coming along.

And they probably saw the 5 white people and the 12 lascars as a kind of threat. But again, there was some kind of sort of confrontations, but no violence at all. They were sort of very inquisitive, no, more than inquisitive, suspicious. But then they did a trade and one man gave them a kangaroo tail, if I remember correctly, and they had their first meat.

But then they met the Walbanga people across and around Bermagui area and Moruya who ferried them across rivers. And they're also from the Batemans Bay area and they gave them dinner. They just said, oh, come over to dinner. The first thing they did was- And they gave them a corroboree. And then I think Clark and his men gave them a bit of a Scottish jig or something, or singing a Scottish song.

And Clark was just mesmerised by them, you know, now he thought, now these are the greatest people on earth. And he said, what, I think they quoted them in saying they possessed a liberality.

Do you want to explain quickly what a corroboree would have been?

I don't know exactly, because I don't know how their corroboree may have differed from anyone else's. There's no exact- So, I wouldn't go so far as to say they're corroboree- They- It's understood that there was some kind of a dance...

So, it's like a welcoming celebration or something, right? Yeah.

...Welcoming celebration. Exactly. It was a welcoming celebration. You are our guests come here. And of course, they did the big inspection of their clothes and their faces and their hair as well. They showed great friendliness to them and looked after them, varied them across rivers, the usual thing.

And then they came- What Clark would do for each- He realised now by the time he meets the Royal Bank, there's totally separate countries here and that he had to give them some kind of present or to show some respect by giving something to their elders or to those who he was meeting.

And he gave them calico and we think they gave them red. We- We're not 100% sure, but we think he gave them red calico because it was understood that when the Aboriginal people, the First Nations people saw the British, they saw them in red coats and they understood that the governor was in red, he was all dressed in red.

And so, the red they understood, was a mark of respect for the strong man or the most important man. And if you were to give them red, red cloth, calico, then that would be considered extremely- A very good thing to do because it's showing respect that you see them as equals.

So, we believe that- He didn't mention the colour, but the anthropologist that I've spoken to, and the expert believes it would have been red because that would have been a highly respected colour by all the groups along the coast.

Would he have done that intentionally or would that have just been dumb luck?

I think it was then he would have given them calico and then probably realised that there were certain coloured cloth that they preferred over the others. And so, he would have said here have their this. And the guy said, oh, not so sure. And then he gave them red and they go, yes, please. So, he was giving- That's all he had to give. I mean, what else could he give? He had nothing but cloth.

Yeah.

It was part of the cargo. The calico was part of the cargo that they brought along and that's all they had to give. And that was their only bargaining power.

Clark would also give speeches when he met a new tribe, and they used to find that that mollified them because he was showing respect by- Even though they couldn't understand a word he was saying, of course. It showed that he was making some kind of signs of, we respect you...

...All it showed- All he needed was to show respect and deference to these people. And nine times out of ten, it worked very well.

That's one of those things that always astonish me with these interactions with Indigenous people in Australian history. How usually, how quickly both sides work out how to have amicable interactions and relationships.

Yeah, I think this is a classic first ever- We're talking about a time when there weren't even people in the- There was nobody on- No white person- I should be very careful.

No settle- This would have been the first ever interaction other than, of course, those in Sydney. And those in Sydney weren't going too well because all Sydney, all the people of Sydney, all the settlers and the convicts of Sydney wanted to do was acquire, acquire, acquire and there were lots of trouble.

But this is a very early example of where people were coming into contact, first contact and it was very amicable, except for when they came to Wandandians, which we can talk about if you like.

Yeah, go for it.

Well, that's around Jervis Bay and the Sussex Inlet and we're getting quite far up New South Wales by this time. This is probably, I'd say over a month. I can't remember exactly, don't quote me, but I think it's been over a month and they're getting pretty bloody tired these guys. Yes, they're getting fed from time to time. But we believe the lascars were in very poor shape.

And the reason they were in more poor shape than the Europeans is because it's understood that the lascars were probably very, very young and they could have been as young as 10 or 11 years old, maybe 15 at the oldest. They were incredibly acrobatic and great sailors. They were every bit as good as European sailors, according to most testimonies of that time.

But they were little kids and they had no body fat. So, if you feed them from time to time, it's just not enough. They need to be fed and like every young person or we're talking about young teenagers. And they couldn't and they start dropping off. And by the time I think they get to the Wandandians around Jervis Bay, about 8 of them are gone. They've just left off.

Now, some- Not- Some fiction writers have said that these people were murdered. We don't know. I believe I've always erred on the side that Clark was a good man, that he just had to keep on, because remember of course, there were 30 something other people waiting for him in Tasmania to be rescued. So, he had...

You also kind of think why would he bother murdering 8 people...?

Who are almost going to die anyway.

When everyone's starving to death, too, right? Unless you were going to eat them and cannibalism them, which there is no, you know, reports of.

That's of course the other- And I just- I physically rebel against that, although I can't prove that I'm right, because there are many things that Clark's diary, which is all we have to go on, is sparse and there's not that much detail in it. But I think he was that- He wasn't a writer. That's how I get it. He wasn't a writer. He was just sort of putting down notes. I don't think he lied. There's nothing about it that feels like dissembling.

And of course, I believe that what happened was correct. And if he was treating the First Nations people with respect, I don't know why he wouldn't treat his own people with fairness and justice, but he couldn't carry people who were sick. It's just impossible.

Yeah.

And he probably thought that they'd been treated well along the way. Hopefully the local people will in some way look after them. We don't know, of course, whether they did or not or that they died, most likely the latter. We don't know because the local people, as I understand it, were letting them through and being kind to them as long as they moved, as long as they moved on.

And these people were staying and that may have been a problem. Not necessarily. But it may have been the problem. So, I was going to say, we get to the Wandandians people. Was there another question you want to ask me or...?

No. Keep going.

Well, this is where the things get more than a little unstuck. They meet the Wandandians and it's hostile- Hostility from the very moment they enter their country. And of course, Clark tries to do the usual things and it just doesn't seem to work. Now, we don't know exactly what happened. We think that perhaps one of the five Europeans was thieving, thieving fish along the way and the Wandandians felt that this needed to be corrected.

So, what happens? The 17 find themselves confronted by about, he said, roughly about 100 very aggressive and hostile Aboriginal man, First Nations men and Clark tries to do a speech. They're not interested. He puts his hand up as a gesture of welcome or please where, you know, to say we're okay here. We've got no weapons.

First thing he knows, a spear goes through his right hand as he put it up. He reflexively puts his left hand up and another spear goes through that. They're little minor spears, but they go straight through his arm, so he finds himself speared.

And then a couple of his other men were speared just a little. Not severely, but they were wounded, you know, wounded quite badly. And of course, the men retreated, the 100 or so warriors retreated. So, it was payback, what it was. And it's very clear to the people I've spoke to, to try and understand what was going on here, that this is payback. This is not any kind- This is punishment, not an attempt to kill them in any way.

From what I understand when learning about these sorts of interactions, it's the type of spear that they're using that kind of determines, right. If it's a clean, sharp skewer like spear that's meant to just pierce. It's only meant to harm. But if it's a jagged one, that's very difficult to pull out. It's meant to kill, right?

Yeah, exactly. And of course, the First Nations people were exquisite spear throwers. They knew exactly where to throw to harm, but not to kill.

The fact that they got both of his hands and no other parts of his body is insane. Right.

It's insane how good, how accurate these people were. And of course, Clark was rather upset. He hadn't expected that. He thought everybody was his friend up the coast, or at least fairly friendly. There's the odd suspicious.

Well, I can't imagine, too. You're in the middle of starving. You've been on a walk for a month, and now both your hands are out of commission.

Yeah. Yeah, exactly. And his mate, his second in command, Thompson speared as well. And Thompson wasn't in a good way. He'd been nearly drowned, I think, a week or so earlier. He was in a bad way. And what happened- Then happened was they walked along and later that day, those 100 men or portion thereof almost shepherd them. They said- They basically surrounded them and said, you've got to go this way.

And so, they marched them off their land, basically. And what Clark said later was, he didn't say it in relation to the Wandandian people that he'd met because he didn't know their names. He did say that one of- The carpenter, he never gives his full name, was thieving fish. Whether that's related to the payback, we can't be 100% sure. But that's what he said.

And if that's the case, they may have been stealing from fish traps that, you know, they weren't allowed to have stolen from or hadn't got permission, etc.

Yeah.

This is classic payback. And we know, of course, that Governor Phillip was paid back. He had a spear through his shoulder on Manly Beach in Sydney for exactly the same reasons. One of the colonists, the settlers, was thieving fish or harassing Aboriginal people in their fishing areas. And of course they have to- The important point is that they have to pay back at the highest level.

And they knew Clark, of course, was the leader. He was the one that came forward. And of course, they knew also that Philip was the leader. So, Philip had to pay for the sins of others, as Clark had to pay for the sins, we believe, of a carpenter. So, they were a pretty motley crew by now. We're talking a month, a month and a half in, and they were getting very weak.

And of course, the Wandandians didn't give them any food, they just marched them off. And...

They gave them food for thought.

Yeah. And by now things were getting pretty desperate. I don't remember the exact sequence of- But it ends up that by the time they reach parts of the- Around the Shoalhaven River, around Nowra, there's only 5 of them left. And that's I think, if I remember correctly, that's 3 Europeans and 2 of the lascars. And one of the lascars- In fact, one of them was not a lascar, it was his personal servant. It was Clark's personal servant.

So, he was an Indian servant. So, one lascar, one servant, and three Europeans still standing. And they wandered- Because Clark could now no longer write. So, we don't get any diary entries here. And all he said was, when- Was later, he said, we walked in a daze in eating whatever we could, drinking from muddy holes for two weeks.

I don't know how they survived. I mean...

I don't know how they didn't get dysentery or whatever from just drinking random water out of puddles and stuff. It's like, how on earth did they survive?

Look, this is just amazing. Look, it's just how they survived until they find themselves about- Around about the Royal National Park, which is south of- I think it's just north of Wollongong. And they come to a little beach where- And by the way, the day before, I should say, two of them dropped out. The carpenter couldn't go on and Thompson, of course, had been wounded and semi-drowned, half drowned. They just couldn't go on.

So, now that 5 had become 3 and they staggered into this little beach called Wattamolla, which is just on- Just south of Sydney. And there's just- They've got nothing left. And then Clark looks up and there it is, a fishing boat, and he yells and he screams and says, please, please. The fishing men come and they take these cadavers, because that's what they were by now, practically living cadavers.

They ferry them all the way straight to the governor's residence. And Clark survived, so there's 3 of them that survive. His manservant and a seaman called Bennett, one of the Europeans, so. And it's an unbelievable story of resilience and a trek. And that's as you ask, it's the most important part of the book.

But there are other parts of the book, too, that I think are important, but you know what, we still ask about.

It is just insane. What do you think the lascars were experiencing throughout this time? Do you want to talk a little bit about them, so describe who they were, why they were involved with some of these sailors coming to somewhere like Australia and what their experience and thoughts may have been like.

Well, they came as- I believe that many of them had been shanghaied, taken from poor families, or if not shanghaied, had elected to go to sea. It's a little bit like all the poor people- What- A person who's poor, who has no prospects, what do they do? They go into the army. Well, the lascars go into the not the Navy, but they form bands and they are taken into syndicates and created this, "Can you give me a crew? We need 35-40 people."

This time they took quite a big crew because they never really had gone- Very few Indian boats had gone- Indian ships had gone that far. So, they needed a large crew. And of course, the lascars were totally expendable. We're talking about, you know, they expected to lose 5-10 along the way. And they did lose 5.

Did the lascars know that? Were they aware of those...

Oh, they would have known they were expendable. They were given half the food that a European was given. They say something like to feed and look after a European sailor, you need one tonne of goods. Whether that be food, whether that be his clothing, whatever. For a lascar, you needed about a third of that. And of course, they'll pay about a third of what Europeans were paid, but they came as a package so they couldn't under-

No one could- No European could understand their argot, their language. They used to sing songs that apparently were very anti-European, it was there any form of rebellion. And they sing songs while they were, you know, furling and unfurling sails, etc. And they were very capable sailors run by the equivalent of a bo's'n, I'm told. They call them a Tindal, and the Tindal was in charge.

And Tindal had- He looked after all the crew, but of course there would have been Europeans- There were a few European sailors on there as well who would have done their own thing and would have probably manned different parts of the boat. And the first- There was the first and second mate, Thompson was a European sailor and Bennett was another one. There's- There may have been others, but Clark never mentions their name.

Anyway, you're asking about the lascars. I think they were sort of shanghaied kids, mostly kids. Some of them would have been older, of course, in their twenties, but a lot of them were kids and a lot of them- They were probably selected on this journey because they were considered the youngest and fittest.

Whereas they didn't realise that there was going to be a walk like this. So, the youngest and fittest aren't the most- Don't always have the most highest amounts of stamina. And that's what came, I believe, came undone. Not that they were massacred by Clark and his Europeans, like others have said. It's complete BS if you ask me, but we won't go there.

So, we don't know an incredible amount about them, except that they were considered expendable. They were basically one step removed from being slaves, I think is probably the way to describe them.

Yeah. Yeah, it does seem- So foreign to it. I'm sort of ashamed that I'd never heard about the lascars prior to reading about them in your book, but they have such a deep place in our history because they were some of the first people outside of the Indigenous Australians to travel such a vast amount of land on foot. Right? If not the first people with the European sailors there.

Peter, isn't it so typical of Australian history that the brown and black people have just been cut out of it? And you know, we reckon, they reckon the first 30 years of the colony, most of the produce that came, came through via India. So, don't tell me that there weren't hundreds of lascars in Australia, in Sydney who would maybe only spend small amounts of time, I'm sure some of them settled.

But they would have been a regular sight on all the boats.

They would have been a regular sight on the boats. There would have been a lot of lascars come to Sydney and any other the newly settled areas as time went on and yeah. Written out as usual, which is what makes me very angry, but I'll try not to go get too angry.

So, tell me a bit about the rum and the sort of issues that were going on. It seemed like there was a lot of tension between the leaders of the colony at the time. Well, Leader, Hunter and his rivals like MacArthur and the the Rum Corps. So, what was sort of going on with these relationships at the time and how was rum used in the colony and how was it, you know, affecting these relationships?

Well, it's a fairly long- I'll try to cut it as short as possible. Basically what happened was after Philip left, the colony was put in the hands of the- Well, it wasn't called the Rum Corps. It's the 102nd Infantry, New South Wales Infantry, if I remember correctly.

And of course they're running the show, they have everything. So, of course, later they decide to make new rules. Under Phillip, they weren't allowed to have land. So, the new rules said you can have everything you want. Just as Philip was leaving, they said, can we get some more grog? The colony obviously needs it.

Let's- The officers will put together money and we'll take a- We'll send a ship off to the Cape and bring back grog and some of the goods that were needed, badly needed because of course the colony was badly in need of lots of things. The grog became the main thing.

And of course they became- They would have obviously seen that grog was everything to all the- Both the convicts and to all the colonists that were there, because there was no form of entertainment or enjoyment. And people just wanted to drink just to remem- Because they were up- They were 12,000 miles away from from their homes. So, of course, grog became a really big thing.

And there was no currency because the people back in London, they thought, what's the point of having a currency in a convict colony? This is not a commercial colony. It's a penal colony. Why should we-? That was- So, suddenly rum becomes the major thing.

And there's an apocryphal story which I love to tell, which is in, I think, early chapters about how the- Whenever a ship came, and there were odd ships that came, the American ships came filled with grog and it became gradually known over the first few years that grog and rum mostly was incredibly important to New South Wales. And of course they had all the money, they had all the power. This is the military, the Rum Corps.

So, they bought all the grog and they didn't allow anybody else. The settlers couldn't go up to the merchants in the ships or the ship captain say, oh, I'd like this. They ran it. So, they had all the power when they had all the grog. There's a great story I love about- And it might be apocryphal, so it may not be true. But they say that when a rum corps officer- A ship would arrive, a Rum Corps officer would say, I need to test your grog, sir.

What he would do? He wouldn't drink it. He would mix it with gunpowder. It was- What was important was not whether the grog- They mix it with gunpowder, then they'd light it. If the grog didn't catch fire he was- They weren't very impressed. That meant it was probably 40% proof rum. If it was over 60% proof, it would probably catch fire. And if it was over 80% proof, the rum itself mixed with gunpowder would explode.

So, what they were looking for was exploding rum because it was extremely high alcoholic content. So, what they would then do is they'd buy the rum. And then they'd water it down 8 to 10 times and then they'd sell it to the colonists at 8 to 10 times the price when it's watered down 8 to 10 times.

This is how they made their money. And then what happened was grog became so important that it lured all the convicts, all the convicts came off any public program. The doctors didn't care about public programs, they just wanted to manage their farm. So, all the convicts became- They took 10 convicts for each officer, and they'd manage their farms and they'd be paid in rum or grog or whatever sort.

And then the settlers, of course, wanted the rum, too. But the prices are so exorbitant, they would say to the officers, I will pledge you half of my, you know, half of my wheat crop next year if you give me XYZ amount of grog. And of course, they said, okay. And then finally the wheat doesn't come. They said, well, I'm sorry, I'm expropriating your entire farm because you haven't paid your debt.

So, see how rum becomes so licit to value. And so, suddenly the officers were becoming the most powerful people. They didn't let anyone. They were the policeman and they were the judges, juries and executioners. They made all the rules. By the time Hunter came along, that's 33 months between Phillip and Hunter, they ran the place in every single way. All the rules were run by the Army to their favour and to the officers favour.

Hunter comes along and says, what's going on here? This is a penal colony, supposedly, and you don't own the convicts. You don't- But then he finds that at every point when he tries to change the law, they just ignore him. So, for the next 5 years, when he came in late 1795 to when- To 1800 during his tenure, he has trouble with a certain man who basically ran the corps but was behind the scenes called John MacArthur.

John MacArthur was a cap- What the Italians and the mafias would say he was a racketeer. He was a grog runner. He ran the whole show. And MacArthur did everything in his power to unsettle and unseat Hunter. I don't want to go into too many of the ways he did it.

Yeah.

He was- But I consider John MacArthur the most evil man of the first 50 years of Australia. I don't know who came more evil than him afterwards. But he was the most manipulative, most corrupt and most hypocritical person I've ever come across within my colonial research. And he had- He gave the first 4 governance through- 4 governance that he was involved with absolute hell.

And then of course we- Of course we know that Bligh challenged him in 1808 and that was the rum rebellion. And of course MacArthur won that and then Bligh was eventually sent home. And so was MacArthur, but MacArthur came back years later, unsullied.

He was said to be the man who brought the merino. In fact, his wife did most of the work and got the merinos back. So, this man who was on the $2 note, the most corrupt person has been, you know, feted by history. And what I wanted to do is I want to go back to what I originally said was when I talked to Mark McKenna, Professor Mark McKenna, I said- I think he said there's not enough story in just the walk itself.

And I thought, well, the story is rum versus the crown.

Yeah.

And the rum corps versus the crown. So, I wanted to make sure that people understood what these people were bringing was this supposed valuable commodity to Australia. What it was that it meant to Australians. Well, not Australians, colonists at that time.

And so, I wanted to give the two sides of it, the desperate need to buy and sell rum, which is, of course Clark and his men trying to get the rum to Sydney and the incredible rigours they went through and what actually rum was being used for.

And it's- That's what the story is about, it's the counter action, the counterpoint between rum and the desire to trade and free trade that the Scots and people like Clark believed in and how it was abused at the other end. So, you've got the two stories working at the same time, and that's how I believe I made "Three Sheets to the Wind" work- I hope, well, people can make their own decisions.

That's how I think it became big enough and strong enough to make it into a decent story that by getting both those aspects.

I think you're doing an amazing job because I love the fact that you give so much context to this story, which I think you obviously said, you know, you're kind of forced to do because there wasn't enough to really flesh out that story of the marooned sailors getting back, all the way back to Sydney.

But I love that you get to learn about sort of all these other characters and this tension going on in Sydney as well as the role of rum and then the broader scope, that sort of issues between the colony and Britain back home and the tension there between the leaders and everything. So, I think you did an amazing job, mate. So, yeah.

Thank you very much, Pete. Yeah. Look, I think if you can just sum it up, you can say, I don't think this part of of Australian colonial life has been very well represented. It's very early. Hunter's never given very much due.

And of course, one of the other points I make is that Clark, who discovered- This can be important, the first man to cross Bass Strait, the first man to see the seals, which became Australia's first primary commodity, seal skins. Awful as it is, it still became our first export. And of course coal around the Wollongong Port Kembla area.

He found it and saw it. He was given no credit for that and he was forgotten by history. I wanted to bring this back because I hate people that have been forgotten. I hate the fact that people are forgotten by history and he hasn't been given his fair due. And I wanted to give him his fair due and the People and Hunter as well.

He's been sort of glossed over as this weekend effectual governor, which he was to some degree, but he had enormous problems to deal with and was very badly resourced and had no support whatsoever. So, I think Hunter did the best he could in a very, very difficult situation. But people can read for themselves. I keep that open, I think. So, as I was saying, in the end, it's a slice of a period.

It's a period piece, if you like, of showing different aspects of a period and hopefully giving a combination that people will say, I really get what Australia was like. Or I hope people will say what that early part of Australia was like, both from an Indigenous and from a European point of view.

Yeah, it's one of the most frustrating things to me, reading about Australian history is just that the fact that we never have a written account from Indigenous people on effectively anything in those early years because obviously none of them were literate or spoke English very well, if at all right, or were, you know, they wouldn't have been taught to read or write anything like that.

So, it's such a shame we never actually get to hear from their own perspectives of what these interactions were like, what they were actually thinking.

I would love to have known what the...

Oh, man.

Of course we would. It's a great gap, isn't it?

So, what, like, last question. What ended up happening to Clark? And what do you think he made of his experiences in Australia?

I'd rather not mention that one, only- Not because I'm trying to be difficult. Because I want people to enjoy the character of Clark and I don't want to sort of say what exactly happened. But I will say this. I will say, I do believe when he came to Sydney he was only half believed. He wasn't listened to. Maybe one or two people listened to him.

Interesting, George Bass and Matthew Flinders listened to him and said, we now know that there is Bass Strait. We have to discover it officially so to speak.

Yeah.

I won't- We don't know very much about him as a man, but my impression is that he was highly disillusioned. Probably physically wrecked by what happened. He left Australia. He left the colony, I should say, within a roughly about two months and went to India. We don't know very much about what he thought.

I think he was disillusioned and unhappy. I thought he'd had a major experience that wasn't understood by the colony at all, except for the parts where they felt, oh, there's something we can do with that, i.e. the coal, i.e. the seal skins and of course acknowledging Bass strait, which would take, I think, 300 miles off their round the world trip, maybe more than that.

A trip down, of course- So, not getting that acknowledgement is just outrageous as usual, the usual thing. We only are interested in official history and things aren't official in somewhere until the government did it. And so interestingly, this just as an aside, Bass is considered the founder of coal in Australia. It's not true.

Clark actually took him there and Bass- But because Bass was part of an official thing, Bass is credited. Who founded Bass Strait, Bass and Flinders himself did it. No, it wasn't, actually. It was Clark who saw it, with Thompson and had and gave an account of it. So, you know, that's why I get angry. But I shouldn't get angry because this- It's these gaps in our history that are allowing me in, so to speak.

And other historians too. We're being allowed in because things weren't mentioned. And this is what's quite crazy about Australian history. We just don't see this Clark as a hero in our book. If he was American, what would- He would have been- There would have been 10 Hollywood movies about him already.

Yeah.

He would have been feted and celebrated. And that's what's sad about this country. We just haven't looked at our own people and the greatness of the people who came here and the things that they did. Unless it's official, quote unquote "official". And that's why Australian's history, when we learn it at school, it's so boring because of the official version, it's not a real version. And that's why I encourage people to read books like mine.

And there are other... (Distorted) ...And what happened in those interactions, really important that we do that. But that, of course, I would say that.

So...

...A really good writer, telling us the truth about what really happened in those times.

Have you found the next gap yet?

I'm not sure what the next gap is going to be. But, you know, Pete, people come at me and say, oh- I get it all the time. Well, my great, great, great grandfather was a convict. You gotta write about him. I said, what did he do? Oh, well, he had a really rough time coming over. Well, he was the first guy to settle Maitland or whatever, and he did big things.

It's got to be much more than that. You know, I've got be able to tell a story.

Did he have a diary?

...There are stories out there. I know there are stories out there that have- Often they're local stories that haven't been given the prominence that I would like to give them. Of course, "The Ghost and the Bounty Hunter" was about William Buckley, and that was such a long Melbourne-type story. It never really filtered through to the rest of Australia. Kind of did, but not really. And I thought, well, and the Clark one was a classic.

How did this not- How did this one get away? And you know, anyone can write to me and say, have you heard the story about this? And you never know. But I'm very selective. It's got to be a great story and it's got to have a meaning and a reason, and it's got to have something that tells us something about ourselves. It's got to be something that says something about the history.

Even if it's tangential, it tells us about the more important history. And you know, that's what's really what I'm looking for. So, please, listeners, send me your ideas. But it's got- I'll be difficult about it, I'll tell you that much.

Well, Adam, thank you so much for coming on the podcast today. Guys, go check out "Three Sheets to the Wind". You'll be able to get it from any good bookstore online or in person. And yeah, I'm looking forward to hearing about the next book and having you back on the podcast, mate.

I love to- I always love to speak to you, Pete. You're one of the better guys to speak with, and easier and I feel very comfortable and thank you for having me on. I really appreciate it.

Man, the pleasure's all mine.

Listen & Read with the Premium Podcast Player

Get more out of every episode!

Premium Podcast members get access to...

- All 900+ podcast episodes including member-only episodes

- Member-only episode video lessons

- Downloadable transcript PDFs & audio files for every episode

Recent Episodes:

AE 1299 – Pete’s 2c: Do You Ring, Call, or Dial Someone on the Phone in Australia?

AE 1298 – Learn English with a Short Story: Day at the Beach

AE 1297 – The Goss: How ‘Dropping In’ Culture Has Changed in Australia

AE 1296 – The Goss: Gorilla Glasses & Dad’s Crazy Zoo Stories – MEMBERS ONLY

AE 1295 – The Goss: Australia’s Most & Least Ethical Jobs

AE 1294 – The Goss: Australia Just Had the Best Aurora in 500 Years!

AE 1293 – The Goss: Should Aussie Schools Ban Homework?

AE 1292 – How Aussie Do Asian Australians Feel? r_AskAnAustralian

Share

Join my 5-Day FREE English Course!

Complete this 5-day course and learn how to study effectively with podcasts in order to level up your English quickly whilst having fun!

Join my 5-Day FREE English Course!

Complete this 5-day course and learn how to study effectively with podcasts in order to level up your English quickly whilst having fun!

Want to improve a specific area of your English quickly and enjoyably?

Check out my series of Aussie English Courses.

English pronunciation, use of phrasal verbs, spoken English, and listening skills!

Have you got the Aussie English app?

Listen to all your favourite episodes of the Aussie English Podcast on the official AE app.

Download it for FREE below!

Want to improve a specific area of your English quickly and enjoyably?

Check out my series of Aussie English Courses.

English pronunciation, use of phrasal verbs, spoken English, and listening skills!

Leave a comment below & practice your English!

Responses